The following is an excerpt from The Furniture of Our Forefathers by Esther Singleton. I collect antique furniture books for reference and often find things of interest I figure others would find of interest. The following is from Part III Early New England (Imported and Hand-made Pieces of the Seventeenth Century).

Formatting may vary as I do these because I'm scanning them and using optical text recognition and really don't have all day, haha.

Starting page 155 and ending page 159. The first plate is the introductory for the chapter page 154.

THERE is a general impression that the early

settlers of New England were a somewhat

fanatical band of Pilgrims who left the vanities

of the world behind them and sought

the wilds of the west in order to live a

simple life in accordance with the dictates

of their own conscience. We must remember, however

that when the Pilgrim's Progress appeared, half a century had

already elapsed since the Mayflower had sailed, and therefore

the Pilgrim's Fathers can scarcely have consciously taken

Bunyan's humble hero as a model. Many of them were far

from humble in station, and they certainly did not despise the

loaves, and, more especially, the fishes of the New England

coasts. They came in the interests of a trading company.

Freedom of worship, moreover, was no stronger inducement

to many to come, than was freedom from oppressive taxa-

tion. Many left their country rather than pay the taxes,

and these No Subsidy men of course took their movables

with them, or had them sent on as soon as they were

settled. The first houses were small arid rude enough, but

very soon we find commodious and comfortable dwellings

filled with furniture that has nothing suggestive of the

pioneer or backwoodsman. A thousand pounds was a

great sum of money in those days, but before 1650 there

were plenty of men in New England who were worth

that amount. Some were even more wealthy. In 1645,

Thomas Cortmore, of Charlestown, died worth £1,255.

Humphrey Chadburn, of York, £1,713, lived till ten

years later. Joseph Weld, of Roxbury, owned £2,028 in

1646, and the possessions of F. Brewster and T. Baton, of-

New Haven, were respectively valued at £I,ooo and

£3,000 in 1643. Opulent Bostonians who were all dead

by 1660 were John Coggan, £1,339; John Cotton,

£I,038 ; John Clapp, £I,506 ; Thomas Dudley, £I,560 ;

Captain George Dell, £I,506 ; William Paddy, £2,221 ;

Captain William Tinge, £2,774 ; Robert Keayne, £3,000 ;

John Holland, £3,325; William Paine, £4,23o; Henry

Webb, £7,819; and Jacob Sheafe, £8,528. It would b.e

an error to assume that the bulk of this wealth was due to

wide domains, for the average plantations in New England

were very small in comparison to those in the South. As a

rule, the personalty far exceeded the realty; land, moreover,

was cheap. George Phillips will serve as a type of

prosperous class of Boston in the early days. He died

in 1644. His estate was appraised at £553. Of this, the

dwelling-house, barn, outhouse and fifteen acres of land

only amounted to £12o, whereas the study of books alone

was worth £7I-9-o. The house contained a parlour,

hall, parlour chamber, kitchen chamber, kitchen and dairy.

The hall was furnished with a table, two stools and a chest.

The parlour contained a high curtained bedstead with

feather bed, a long table, two stools, two chairs and a chest

#an made comfortable with six cushions) and a valuable

silver "salt" with spoons. In the other rooms were five

beds, four chests, two trunks, one table, one stool, bed and

table linen, and kitchen stuff. A good example of a

kitchen, that of the Hancock House, Lexington, Mass.,

faces page 155.

William Goodrich, of Watertown (died 1647), is an

example of the settler of moderate means. His furniture

is evidently of the plainest kind and probably made by a

local joiner, since his cupboard, chest, two boxes, chair table,

joint stool, plain chair and cowl, are valued at only

eighteen shillings. While the flock bed with its furnishings appraised much higher.

The latter, however, is worth more than half as much as his dwelling house and five and

are-half acres of planting land in the township, three acres

of remote meadow and twenty-five acres of "divident,"

which total only £I0 altogether.

The wealth of the settlers consisted, in many cases, of

English goods" including all kinds of clothing, cotton,

linen, ``woolen and silk stuffs; and tools, implements, vessels

and utensils of iron, pewter, brass, wood and earthen.-

ware. It is surprising, however, on scanning the numerous

inventories of merchandise, to see how few articles of

furniture were on sale in the various stores. The manifest

conclusion is that such furniture as was not brought

in by the immigrants was either specially made here or

ordered from local or foreign agents. Henry Shrimpton,

of Boston, who died in 1666 with an estate of £12,000,

had goods to the value of about £3,3oo to supply the

needs of the community, but practically none of his stock was wooden furniture.

Thomas Morton, writing in J632, says:" Handicraft,..men there were but few, the Tumelor or Cooper, Smith and Carpenters are best welcome amongst them, shopkeepers there are none, being supplied by the Massachusetts merchants with all things they stand in need of, keeping here and there fair magazines stored with English good but they set excessive prices on them, if they do not gain Cent per Cent, they cry out that they are losers."

The first houses at Plymouth were constructed of rough-hewn timber with thatched roofs and window panes of oiled paper. The chimneys were raised outside the walls, and the hearths laid and faced with stones and clay. Edward Winslow, who next to Bradford was the leading spirit in the colony, writes in 162 I : "In this little time that a few of us have been here, we have built seven dwelling houses and four for the use of the plantation, and haYe made preparations for divers others." In the same letter he enjoins his friend to bring plenty of clothes and bedding, fowling-pieces and "paper and linseed oil for your windows with cotton yarn for your lamps."

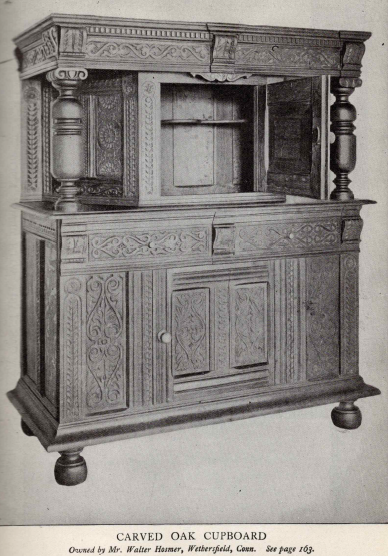

The following plate is from page 159.